Language Change

... assessed quantitatively

This is 3-year project, founded by the National Science Centre (OPUS 2013/11/B/HS2/02795), entitled “Przebiegi zmian gramatycznych i leksykalnych w historii języka polskiego – metody korpusowe i kwantytatywne w językoznawstwie diachronicznym” (“Course of grammatical and lexical changes in the history of the Polish language – corpus-driven quantitative methods in diachronic linguistics”), aimed at an investigation of grammatical and lexical changes, focusing on trends and dynamics of changes in the middle and modern Polish period. What makes this approach innovative is an extensive use of methods developed within the fields of quantitative and corpus linguistics. A purpose-built diachronic corpus of Polish (ca. 12 mln word tokens covering the years 1380–1850) has been analysed in a statistical manner in order to observe various changes in the course of development of the Polish language.

The second objective (considered even more important by the authors) is to create statistical tools which will facilitate description of the course of linguistic changes, their dynamics, and particularly their parallel coocurrences. We aim at developing a methodology which will combine a diachronic large-scale analysis with an automatic identification of the specific grammatical and lexical features responsible for a language change.

The team of the project includes:

- Rafał L. Górski (PI)

- Magdalena Król

- Maciej Eder

Below, we briefly present – as appetizers of full-length papers to appear – two studies conducted within the project. The first study aims at modeling isolated language changes using logistic regression, whereas the second introduces a new method of assessing the dynamics of language change en masse.

Piotrowski’s law

One can hardly imagine a different picture of a language change than that it starts with a small (possibly sociologically or spatially restricted) group of speakers, gaining gradually more and more users over time, even if the opposition of conservative speakers slows down the change. After the first period of slow dissemination, the change accelerates, until newly introduced form is broadly accepted by language users. The recessive form gradually becomes rarer, and finally dies out, partly because its adherents die as well. Certainly, it takes time for a change to be complete.

On theoretical grounds, a change in language can follow two main scenarios. Firstly, it can be an innovation that affects a language system without displacing any already-existing forms. In general, newly introduced vocabulary falls into this category (e.g. the emergence of the word nettiquette in the system does not force the word etiquette to disappear). The second scenario occurs when a new form simply replaces the old one, e.g. the degree to which the form burned (the past form of the verb to burn) spreads in English, by definition equals to the withdrawal of the irregular form burnt. In mathematical terms, the probability of finding a new and on old form (denoted as n and o, respectively) in such a scenario is P(n) = 1 – P(o), which also implies that P(o) = 1 – P(n). Consequently, the joint frequency of the two forms might remain constant over the centuries, while their mutual proportions usually vary to a significant degree.

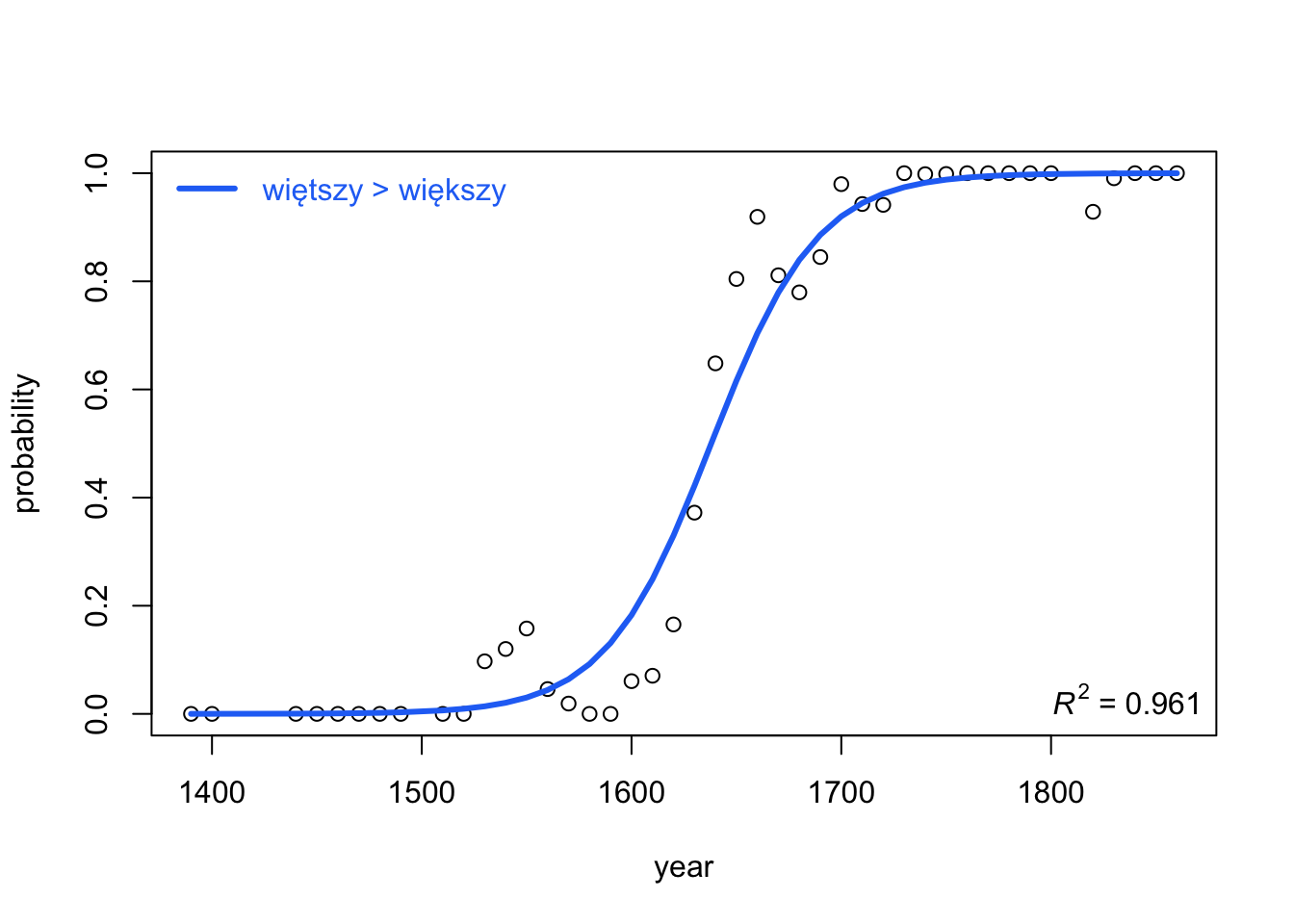

This study explores language change that can be modelled using logistic regression, which in the context of historical linguistics is often referred to as Piotrowski’s law. The examples are drawn from the Polish language, that is a few changes reported by the textbooks on the history of Polish to have taken place between mid-15th and mid-19th centuries, are used here to validate the theoretical models.

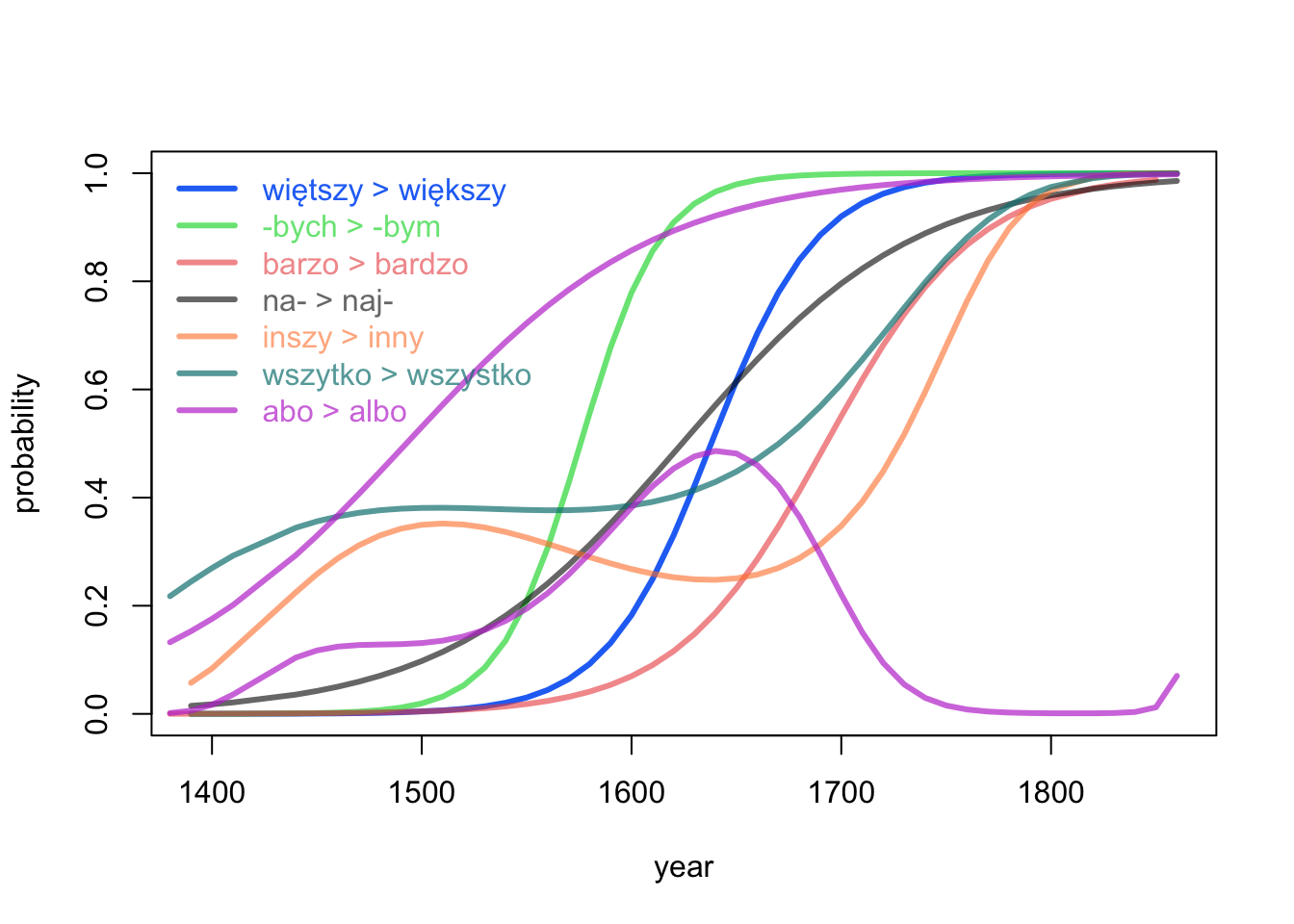

Interesting as it is, such a model cannot overcome the problem of possible co-occurrences of several language changes. In our approach, we propose to combine multiple logistic regression models into a one bigger picture. An exemplary plot of such a combination is shown in Fig. 2.

The dynamics of language change

This study aims to capture the dynamics of language changes without manual pre-selection of the features that might be responsible for the changes. Our approach was to analyze a fairly large set of 1,000 most frequent words without any further filters. Arguably, in such a big set one should find a few dozens of function words, in the number of types greatly outweighted by content words.

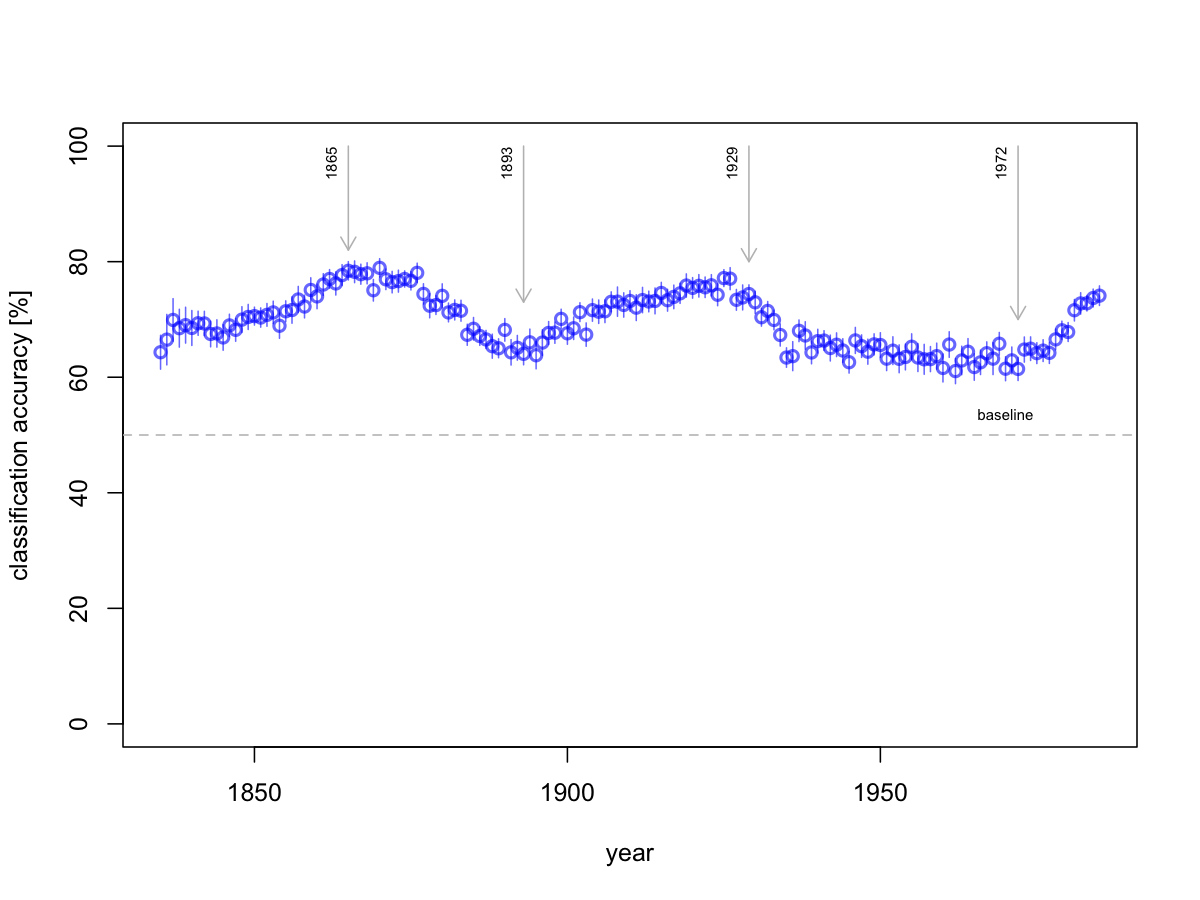

The most natural choice of a way to assess the discriminative power of numerous features at the same time is to apply one of the multivariate methods. To this end, used here was iterative procedure of automatic text classification. Its underlying idea is fairly simple: first, we formulate a working hypothesis that a certain year – be it 1835 – marks a major linguistic break. The procedure randomly picks n text samples written before and after the assumed break; the samples then go into the ante and post subsets. In this study, we covered a period of 20 years before and after the assumed break (with an additional gap of 10 years), 500 text samples of 1,000 tokens were harvested into each of the subsets. To give an example: for the year 1835, 500 random samples covering the time span 1810–1830 are picked into the first subset, and another 500 samples from the years 1840–1860 into the second subset. Next, both subsets are randomly divided into halves, so that the training and test sets contain 500 samples representing two classes (ante and post) each. Then we train a supervised classifier – in this case, Nearest Shrunken Centroids – and record the cross-validated accuracy rates. We then dismiss the original hypothesis, in order to test new ones: we iterate over the timeline, testing the years 1836, 1837, 1838, 1839, … for their discriminating power. The assumption is simple here: any acceleration of linguistic change will be reflected by higher accuracy scores.

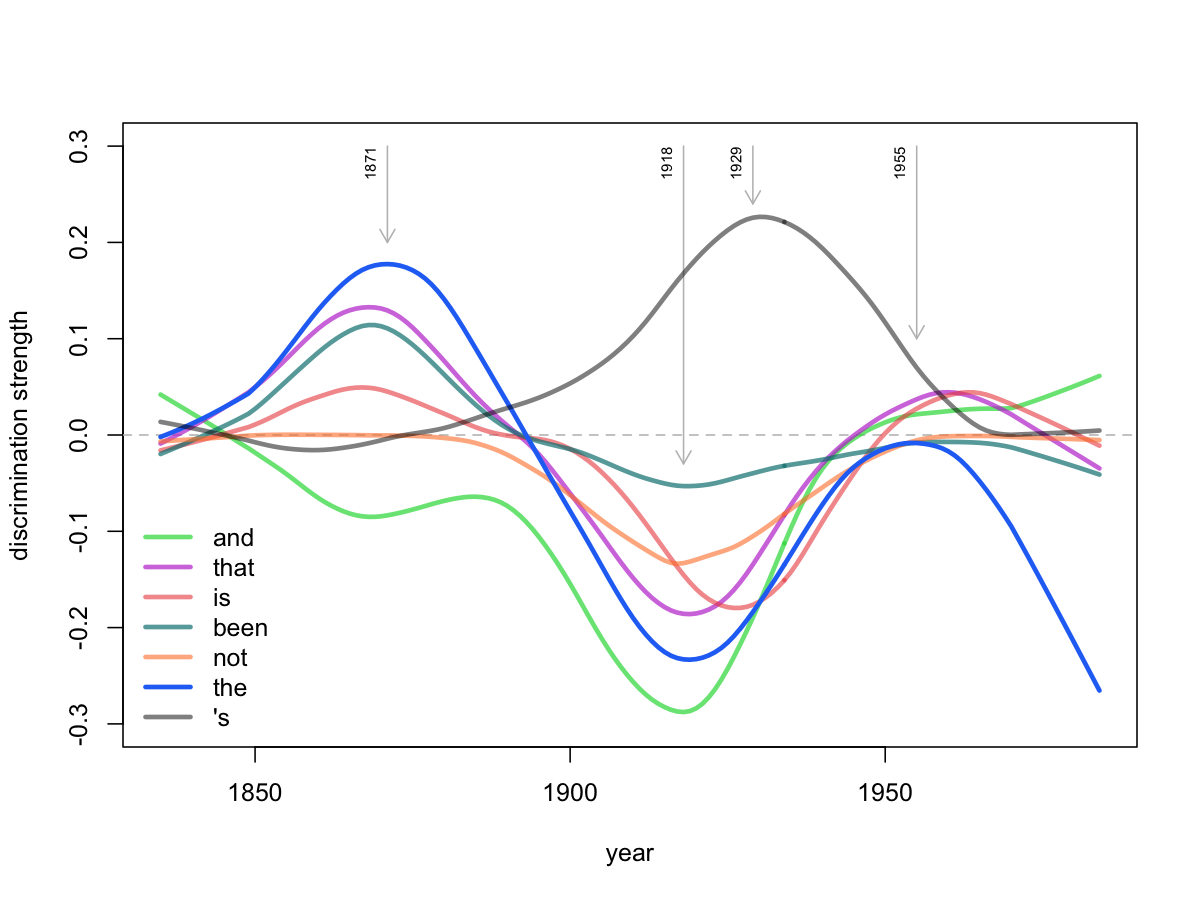

Despite the general above picture, it is individual trajectories of the high-impact words that are quite interesting. In Fig. 4, you can observe a collinearity of function words: the, and, that, is, been, as opposed to the possessive ’s. These function words seem to have impacted the language change at the turn of the 19th century.

Publications

Górski, R. L. and Eder, M. (2022). Modeling the dynamics of language change: logistic regression, Piotrowski’s law, and a handful of examples in Polish. Journal of Quantitative Linguistics doi:10.1080/09296174.2022.2151208, preprint: https://arxiv.org/abs/2104.06324.

Górski R. L., Król, M. and Eder, M. (2019). Zmiana w języku. Studia kwantytatywno-korpusowe. Kraków: IJP PAN. (Cf. the book’s repository).

Król, M., Derwojedowa, M., Górski, R. L., Gruszczyński, W., Opaliński, K., Potoniec, P., Woliński, M. Kieraś, W. and Eder, M. (2019). Narodowy Korpus Diachroniczny Polszczyzny. Projekt. Język Polski, 99: 92–101.

Górski, R. L. (2018). Metody korpusowe i kwantytatywne w językoznawstwie historycznym. In Stalmaszczyk, P. (ed.) Metodologie językoznawstwa. Od diachronii do panchronii. Łódź: Wydawnictwo UŁ, pp. 65–81.

Eder, M. (2018). Words that have made history, or modeling the dynamics of linguistic changes. Digital Humanities 2018: Book of Abstracts. Mexico City, pp. 362–65, https://dh2018.adho.org/en/abstracts/.

Górski, R. L. (2017). Prepositions, frequency and the periodization of Polish. In Stluka, M. and Škrabal, M. (eds.) Liſka a czban : sborník příspěvků k 70. narozeninám prof. Karla Kučery. Praha: Nakladatelství Lidové, pp. 82–89.

Eder, M. and Górski, R. L. (2016). Historical linguistics’ new toys, or stylometry applied to the study of language change. Digital Humanities 2016: Conference Abstracts. Kraków: Jagiellonian University & Pedagogical University, pp. 182–84 http://dh2016.adho.org/abstracts/398.

Eder, M. (2016). Słowa znaczące, słowa kluczowe, słowozbiory – o statystycznych metodach wyszukiwania wyrazów istotnych. Przegląd Humanistyczny, 60(3): 31–44.

Eder, M., Klapper, M. and Kołodziej, D. (2015). Dawna polszczyzna i nowe technologie: testowanie metod przetwarzania języka naturalnego na materiale polskiego piśmiennictwa od średniowiecza po wiek XX. Biuletyn Polskiego Towarzystwa Językoznawczego, 71: 189–202.

Recent presentations

link to “Qualico 2018” presentation

link to “Digital Humanities 2018” presentation (a short version of the above one)

link to a presentation on the Piotrowski’s law (in Polish).