Gallus Anonymous

Who wrote ‘The Polish Chronicle’?

The 13th-century work entitled Gesta principium Polonorum (The Deeds of the Princes of the Poles), also known as Chronica Polonorum (The Polish Chronicle), is one of the earliest written documents on the history of Poland. It is also regarded to commence the Polish literary tradition, even if the text itself is in Latin. However, despite the importance of the chronicle, very little is known about its author. Traditionally called “Gallus” (a person from Gaul, or France) and probably a non-Pole, he seems to have been a benedictine monk. A few hypotheses about the author’s origin have been formulated, with the claim about him being a “Gallus” surfaced as early as in the 16th century. Then came the Hungarian hypothesis in the 19th century, followed by the Venetian hypothesis as formulated in the 1960s by Danuta Borawska (Borawska, 1965), and recently extended by Tomasz Jasiński. The Venetian theory is based on some textual similarities observed between Translatio Sancti Nicolai by an author referred to as the “Monk of Lido” (Monachus Littorensis) and the Chronicle.

In his original study, Jasiński tested rhythmical patterns of Gallus’ sentence endings and found striking similarities with those of Monk of Lido (Jasiński, 2005). The findings were then extended by some extra-textual evindence, in later studies (Jasiński, 2006; 2008; 2009). A motivation to undertake the present study, was the fact that the simple stylometric method proposed by Jasiński was carried out in isolation from the existing state-of-the-art attribution methodology.

The outcomes of the experiments have been published in the following paper:

Eder, M. (2015). In search of the author of “Chronica Polonorum” ascribed to Gallus Anonymous: A stylometric reconnaissance. Acta Poloniae Historica, 112: 5-23, [pre-print].

A slightly extended version in Polish is also available (Eder, 2017). Below you will find a few key findings (or, an appetizer).

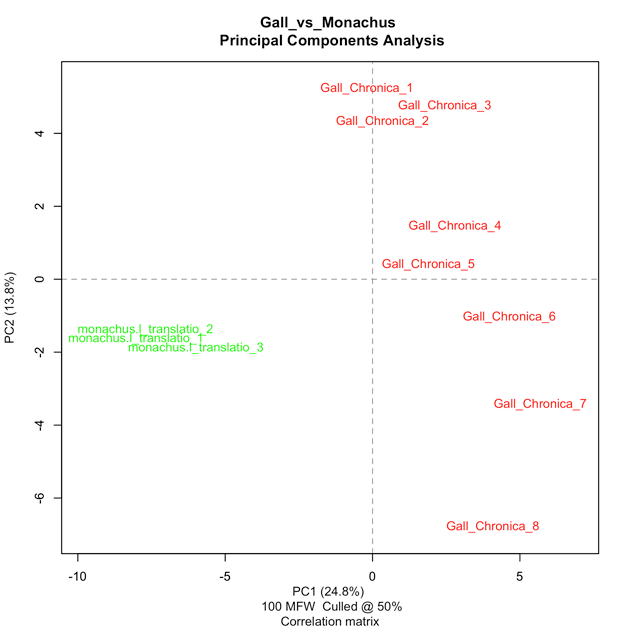

Fig. 2 shows a direct comparison of the Translatio and the Chronica against each other, with no reference (yet) to the comparative corpus. Both texts have been divided into sections of 10,000 words each. As a result, Translatio is represented by three samples, and the Chronicle by eight samples: the first three almost exactly coinciding with Book I, samples 5, 6 and a part of 7 belonging to Book II, whereas a lion’s share of sample 7 and the whole of 8 forming Book III. The concentrated distribution of the Translatio samples is quite striking. Most interestingly, however, observable here is an evolution – from the earliest to the latest fragments of the work, with a fairly clear division into Book I (samples 1–3, drifting in the upper area), Book II (the three samples at the centre) and Book III (the less clearly separated samples 7 and 8). This might obviously bring about new findings with regard to the time when the respective sections of the Chronicle were written.

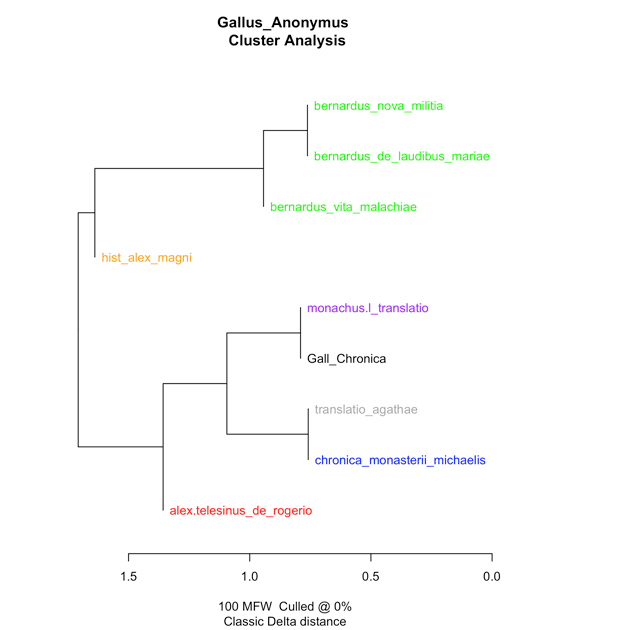

Next comes a comparison of the Chronicle against a number of texts that were written roughly at the same time. A sample dendrogram for 100 most frequent words, the Delta distance measure and Ward’s linkage algorithm is shown in Fig. 3.

The above dendrogram shows rather clearly that a discrete branch hosts three treatises by Bernard de Silvestris – properly recognised as written by the same author – whereas on another branch, the Chronicle’s closest neighbor is Monachus’s Translatio. This is a considerable, though not decisive, argument in support of the supposed stylistic uniformity of Gallus and Monachus.

Since cluster analysis might be very sensitive to input parameters of the model, it is usually better to use a more sophisticated technique, e.g. Bootstrap Consensus Networks. In Fig. 4, a network of 159 Latin texts, including both Gallus and Monachus, has been shown. The right side of the network exhibits mostly historical works – those by Julius Caesar, Tacitus, Sallust, Florus, and others. In terms of the authorship of the Chronicle, fundamental are the works which are directly connected to the Gallus’ work, be it a stronger or weaker link. All such similarities are marked in colour, and the relevant nodes labelled. These include, starting from the most distant relationships: Sallust’s Caligula and Res Gestae Divi Augusti, Ambrose’s Letters (these being very strongly connected with a number of other nodes), Dante’s Monarchia, St. Bernard of Clairvaux’s Life of St. Malachy of Armagh, Albert of Aachen Historia Ierosolimitana, and Augustin Tünger’s Facetiæ.

Gallus’ Chronicle demonstrates some stylometric affinity with these works, yet none of them appears to be its closest neighbor. Such close neighbors include: Chronicon Coenobii Sancti Michaelis de Clusa (11th century), The Alexander Romance by Pseudo-Callisthenes, The Ecclesiastical History of the English People by Beda Venerabilis, Alexander of Telese’s The Deeds Done by King Roger of Sicily and, lastly, the Translatio by Monachus Littorensis, which is associated with the Gallus’ work due to an extremely strong stylistic similarity: in the other sections of the plot, similarly strong connections are those between the works written by the same author (e.g. the instances of Cicero, Vitruvius, or Varro).

An obvious conclusion comes to mind: the similarity between Gallus and Monachus is so evident that no accidental concurrence can be the case. As long as no better prospective author is proposed, the Venetian background hypothesis will be difficult to undermine.

References

Borawska, D. (1965). Gallus Anonim czy Italus Anonim. Przegląd Historyczny, 61: 111–20.

Eder, M. (2015). In search of the author of “Chronica Polonorum” ascribed to Gallus Anonymous: A stylometric reconnaissance. Acta Poloniae Historica, 112: 5-23, [pre-print].

Eder, M. (2017). Autorstwo „Kroniki” Anonima zwanego Gallem w świetle badań stylometrycznych: rekonesans. In Dąbrówka, A., Skibiński, E. and Wojtowicz, W. (eds), Nobis Operique Favete. Studia nad Gallem Anonimem. Warszawa: IBL PAN, pp. 59–74.

Jasiński, T. (2005). Czy Gall Anonim to Monachus Littorensis? Kwartalnik Historyczny, 92(3): 69–89.

Jasiński, T. (2006). Rozwój średniowiecznej prozy rytmicznej a pochodzenie i wykształcenie Galla Anonima. In Sikorski, D. A. and Wyrwa, A. M. (eds.), Cognitioni gestorum. Studia z dziejów średniowiecza dedykowane Profesorowi Jerzemu Strzelczykowi. Poznań and Warszawa, pp. 185–93.

Jasiński, T. (2008). O pochodzeniu Galla Anonima. Kraków: Avalon.

Jasiński, T. (2009). Die Poetik in der Chronik des Gallus Anonymus. Frühmittelalterliche Studien. Jahrbuch des Instituts für Frühmittelalterforschung der Universität Münster, 43: 373–91.