Elena Ferrante

Who’s behind that pseudonym?

Elena Ferrante is an Italian writer who does not exist as a person, at least a person bearing that name. Still, someone obviously has been writing her novels. In 2016, an Italian investigative journalist followed the novels’ royalties and announced that they seem to be going to Anita Raja, the Italian translator from the German of Christa Wolf. Raja said this was not true, but things became quite heated also because her husband is Domenico Starnone, a Neapolitan writer (as “Ferrante” always seemed to be) – he has already been mentioned as another possible suspect.

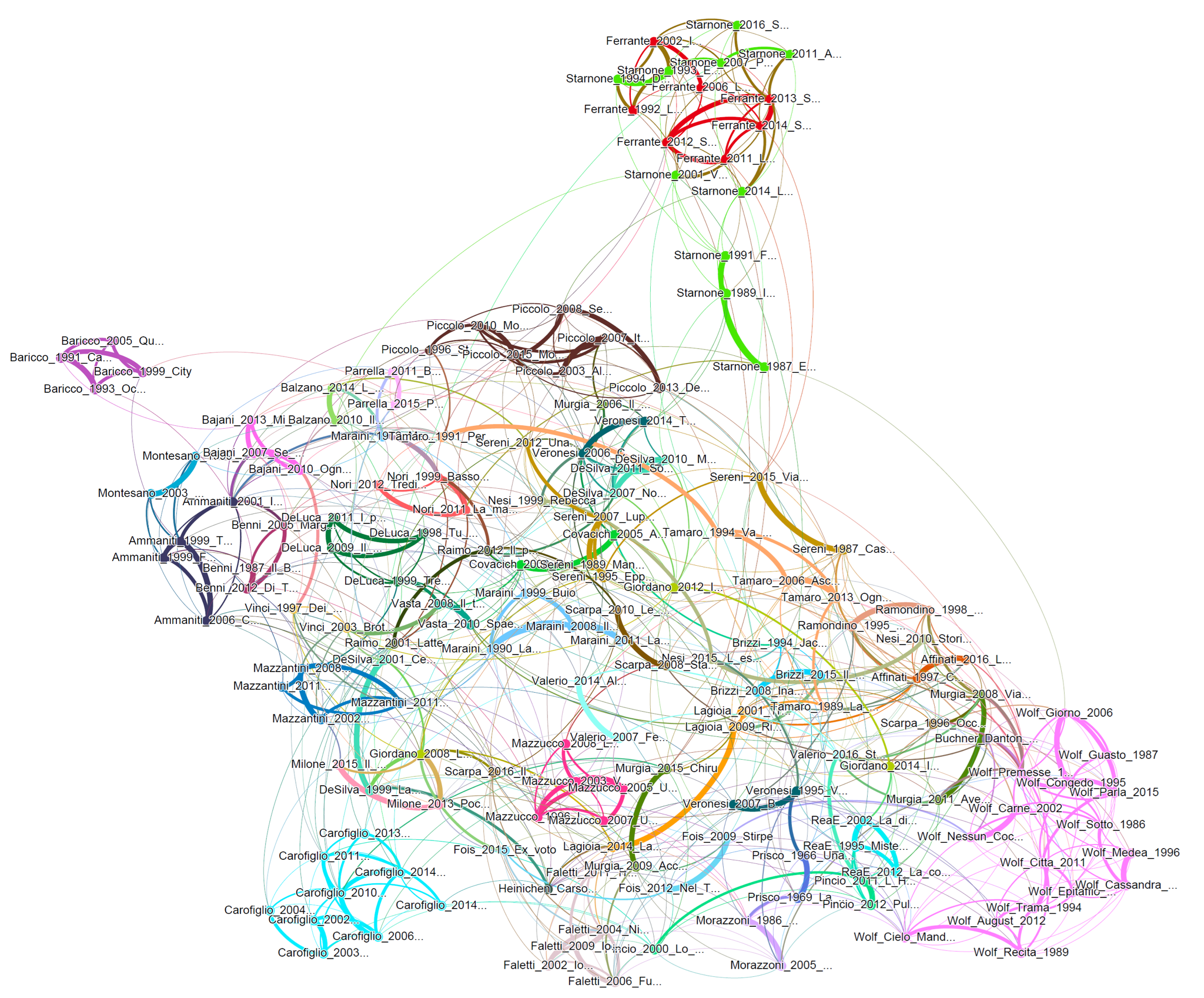

To finally solve this riddle – a very major one in modern Italian literature – the University of Padova, represented by Profs Arjuna Tuzzi and Michele Cortelazzo, organized a workshop called “Drawing Elena Ferrante’s Profile”, which took place in September 2018; they also provided a 150-book electronic corpus of Ferrante and many other suspect Italian writers. Two members of CSG were invited to the workshop together with eight other stylometrists from several countries. Despite using different methods and approaches to authorship attribution, all fingers pointed to Domenico Starnone. Judge for yourselves: in a network analysis of the above-mention Italian corpus, only two authors clustered away from the rest, and these two clustered together: Ferrante and Starnone, in very strong support of the Starnone hypothesis. At the same time, it is worth noting that the translations by Raja are nowhere close to Ferrante.

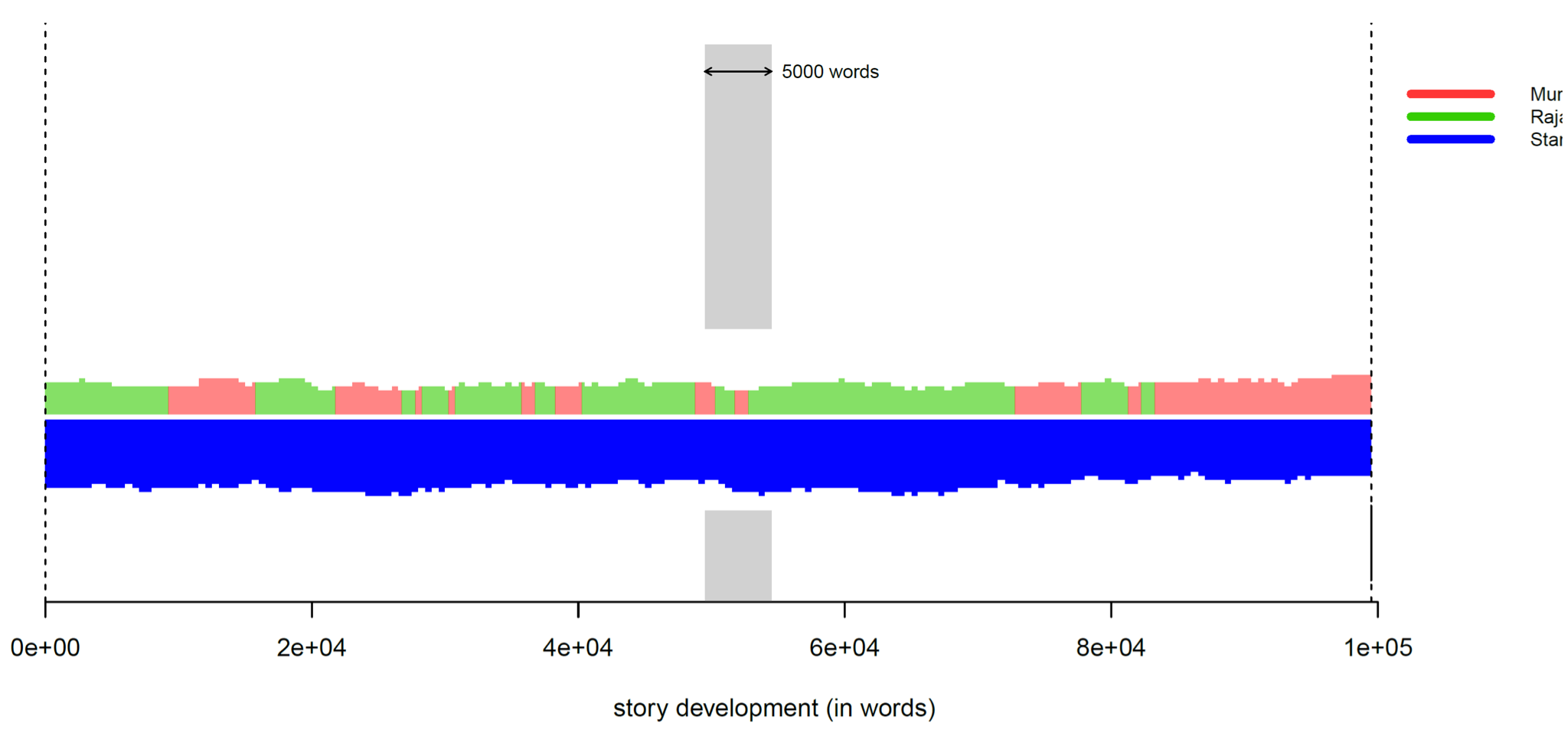

Yet this creates a problem: what if Raja is not visible in this attribution because all we have to go by in establishing her stylometric thumbprint are her translations of another person’s work rather than her real personal traits. This cannot be answered with any certainty. There is still another possibility: Starnone and Raja are in this together, so an attempt was made to look into individual texts by Ferrante to look for possible Raja/Starnone fragments. While the above caveat still remains – Raja’s “signal” can only be represented by her translations of Christa Wolf – the clearly uniform appearance of that of Starnone as the strongest stylometric component over the entire length of a novel by Ferrante (the diagram below shows this for L’Amica geniale) brings us perhaps a little closer to some certainty.

The Padova workshop and its findings made quite a stir in Italy and abroad. La Repubblica reported at one and at length, and so did local Padovan news. TA NEA, a major Greek newspaper, went so far as to publish a picture of some of the researchers involved (including both CSG members). Italian state TV, RAI Cultura, recorded an interview; another appeared in the Dutch De Volkskrant; and Poland’s Gazeta Wyborcza also ran a broader story on the recent Polish contributions in stylometry. Even later, Treccani reviewed the post-workshop (open-access!) volume edited by Arjuna and Michele (link below). Both Raja and Starnone continue to negate all responsibility. Starnone even said, “I. AM. NOT. ELENA. FERRANTE.”

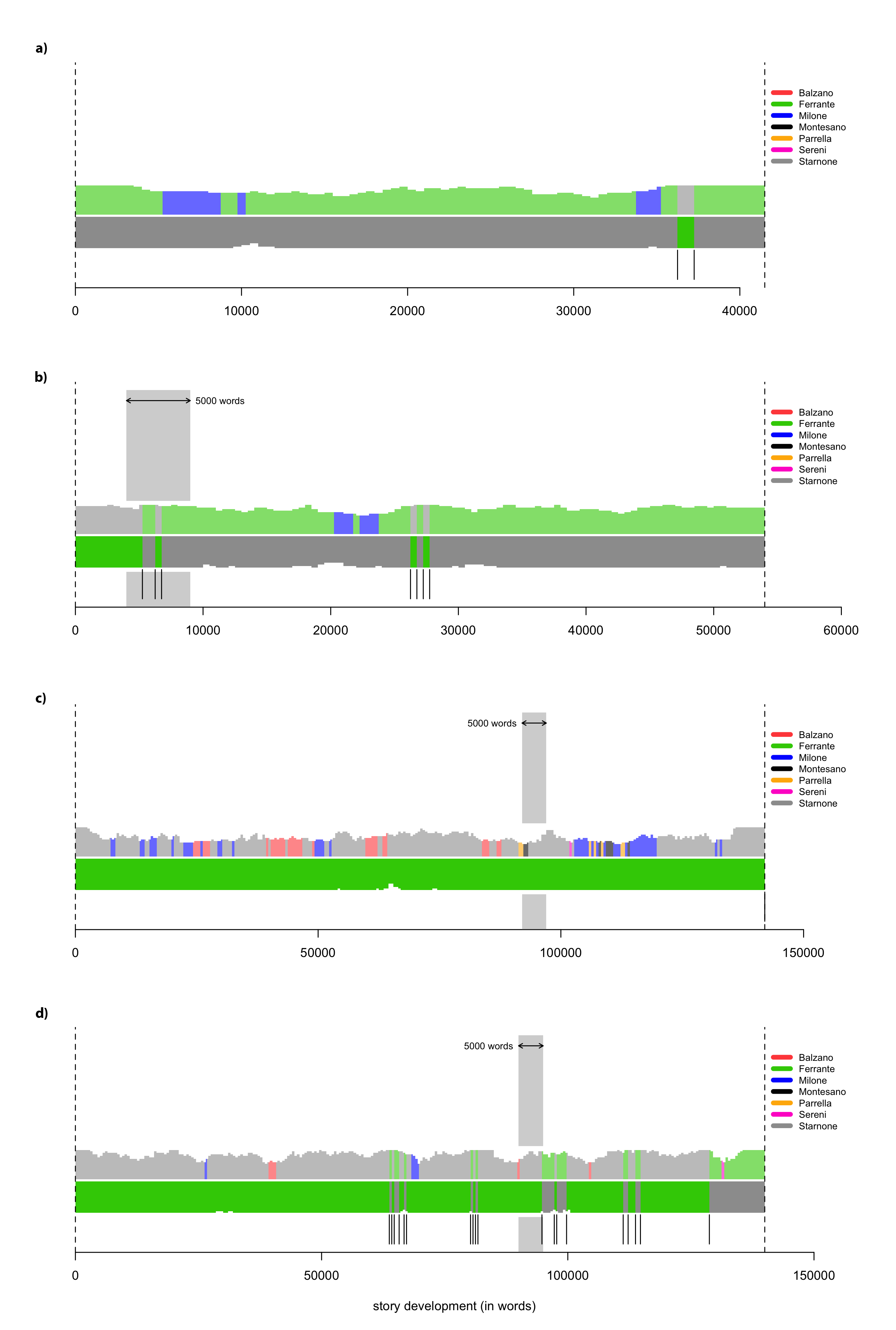

Now, what if we assume that Starnone is right, and HE. IS. NOT. FERRANTE? What if we assume that whenever Starnone writes under the pseudonym, he is not himself anymore, in the sense that he is able to mimic a distinct authorial signal? What if there are indeed two different personae, the actual Starnone and a virtual “Ferrante”? To further explore the above issue, an additional series of tests have been performed. Again, the Rolling Stylometry technique has been used; this time, however, the training set contained the works a few actual authors, and the works by Ferrante. Needless to say, the novels by Starnone and Ferrane were marked as two distinct classes.

The results are shown in Fig. 3a–d (four novels out of seven); the analyzed novels by Ferrante are ordered chronologically. Arguably, a clear pattern appears: while the early novels show little similarity with the assumed virtual “Ferrante”, the late works are assigned to this class with more and more confidence of the classifier. Almost all of the segments of L’amore molesto (1992) are classified as “Starnone”. The voice of the virtual “Ferrante” is more noticeable in I Giorni dell’abbandono (2002). In La figlia oscura (2006) the share of segments by “Ferrante” is roughly equal to those of “Starnone”. In the novel L’amica geniale. Infanzia, adolescenza (2011) the style of “Ferrante” becomes predominant, which is even more visible in Storia del nuovo cognome (2012). This novel is a triumph of the virtual author: all of the segments have been attributed to the class “Ferrante”. Apparently, Domenico Starnone demonstrates, particularly in his late works, the ability to differentiate his own stylistic profile and the voice of his alter ego.

Rybicki, M. (2018). Partners in life, partners in crime? In Tuzzi, A. and Cortelazzo, M. A. (eds), Drawing Elena Ferrante’s Profile. Padova: Padova University Press, pp. 111–122, http://www.padovauniversitypress.it/publications/9788869381300.

Eder, M. (2018). Elena Ferrante: a virtual author. In Tuzzi, A. and Cortelazzo, M. A. (eds), Drawing Elena Ferrante’s Profile. Padova: Padova University Press, pp. 31–45, http://www.padovauniversitypress.it/publications/9788869381300.

Check also this blog post by Jan Rybicki, featuring the workshop “Drawing Elena Ferrante’s Profile”, organized by Arjuna Tuzzi at the University of Padua, Italy, in September 2018.

The outcomes of the workshop were gathered in a book published by Padova University Press.