From texts to topics, with some NLP in between

In this post I describe a step-by-step procedure of training a topic

model in R, using the package topicmodels. Since in most situations

the corpus needs to be loaded from particular files, and moreover, since

in many languages lemmatization is welcome if not necessary, the post

discusses using the package udpipe to perform the NLP tasks

(lemmatization and named entities detection), followed by preparing a

document term matrix, and then training a topic model. As an example, a

small corpus of the Greek New Testament will be used. It is assumed that

particular documents are stored as simple raw text files in a subfolder

corpus; it is also assumed that the files use UTF-8 encoding. The

corpus used in this tutorial, some additional files, and also a source

code of this very document (Rmd notebook), can be downloaded from a

GitHub

repository.

Lemmatization: a toy example

First, we need to activate1 the package udpipe to perform NLP

tasks, and then to download a language model, in our case one of the two

Ancient Greek models2. The model will be put into a temporary

directory, which is convenient – no need to remember where it is stored

– but it will require the model to be downloaded on each R session:

library(udpipe)

udmodel = udpipe_download_model(language = "ancient_greek-proiel",

model_dir = tempdir())

Assuming that the texts are stored within the working directory, in the

subfolder corpus, we need to list the files in that subfolder:

text_files = list.files(path = "corpus")

Before we discuss how to massively analyze all the texts from the

subfolder corpus, let’s take a breath and look at the NLP step alone,

as applied to a single text. This is going to be the first text in the

said subfolder, namely act.txt (containing the Acts). We

read the text, and then we collapse all the paragraphs to one long

string of words:

current_text = readLines("corpus/act.txt", encoding = "UTF-8")

current_text = paste(current_text, collapse = " ")

Now the tasty moment follows. We morphologically analyze the input text, using the currently downloaded language model as discussed earlier in this post:

parsed_text = udpipe(x = current_text, object = udmodel)

The resulting object parsed_text contains a table, in which the rows

represent subsequent tokens of the input text, while the columns provide

information about lemmas, grammatical categories (or POS tags),

dependencies, and so on. Let’s have a look at most relevant columns (7th

through 12th) of the first 25 rows:

parsed_text[1:25, 7:12]

## term_id token_id token lemma upos xpos

## 1 1 1 1 1 NUM Ma

## 2 2 2 1 1 NUM Ma

## 3 3 1 Τὸν ὁ DET S-

## 4 4 2 μὲν μέν ADV Df

## 5 5 3 πρῶτον πρῶτος ADJ Mo

## 6 6 4 λόγον λόγος VERB V-

## 7 7 5 ἐποιησάμην ἐποιησάμην VERB V-

## 8 8 6 περὶ περί ADP R-

## 9 9 7 πάντων, πάντων, VERB V-

## 10 10 1 ὦ ὦ INTJ I-

## 11 11 2 Θεόφιλε, Θεόφιλε, VERB V-

## 12 12 3 ὧν ὅς PRON Pr

## 13 13 4 ἤρξατο ἄρχω VERB V-

## 14 14 5 ὁ ὁ DET S-

## 15 15 6 Ἰησοῦς Ἰησοῦς PROPN Ne

## 16 16 7 ποιεῖν ποιέω VERB V-

## 17 17 8 τε τε CCONJ C-

## 18 18 9 καὶ καί CCONJ C-

## 19 19 10 διδάσκειν διδάσκω VERB V-

## 20 20 11 2 2 NUM Ma

## 21 21 12 ἄχρι ἄχρι ADP R-

## 22 22 13 ἧς ὅς PRON Pr

## 23 23 14 ἡμέρας ἡμέρα NOUN Nb

## 24 24 15 ἐντειλάμενος ἐντειλάμενος VERB V-

## 25 25 16 τοῖς ὁ DET S-

Please keep in mind that some of the columns might look different

depending on the model you’re currently using. E.g. the column xpos,

providing information about positional parts of speech, depends heavily

on particular grammar used to train a given model. However, the columns

that are relevant for our task are quite uniform, particularly the

column with the original word forms (named token), the column with

lemmatized words (named lemma) and the column with grammatical

categories, or parts-of-speech tags (named upos). Please also note

that the 9th line the table was not correctly parsed by the model; the

token πάντων (each/every) received the label VERB rather than ADJ (a

similar situation can be spotted in the 11th line). For some reason the

model appears to struggle with punctuation marks. It would be wise,

then, to remove all the commas before invoking udpipe, and indeed it

improves the model’s performance significantly. I am not introducing

this step, however, because it doesn’t seem to be relevant for several

other language models.

It is quite straightforward to get the lemmatized text, simply by taking a respective column:

parsed_text$lemma

In order not to clutter the screen, the above line of code was not executed. Here’s the beginning of the same text, i.e. its first 100 elements:

parsed_text$lemma[1:100]

## [1] "1" "1" "ὁ" "μέν"

## [5] "πρῶτος" "λόγος" "ἐποιησάμην" "περί"

## [9] "πάντων," "ὦ" "Θεόφιλε," "ὅς"

## [13] "ἄρχω" "ὁ" "Ἰησοῦς" "ποιέω"

## [17] "τε" "καί" "διδάσκω" "2"

## [21] "ἄχρι" "ὅς" "ἡμέρα" "ἐντειλάμενος"

## [25] "ὁ" "ἀποστόλος" "διά" "πνεύμα"

## [29] "ἁγίος" "ὅς" "ἐκλέχομαι" "ἀνελήμφθη"

## [33] "3" "ὅς" "καί" "παρέστησεν"

## [37] "ἑαυτοῦ" "ζῶ" "μετά" "ὁ"

## [41] "πάσχω" "αὐτός" "ἐν" "πολύς"

## [45] "τεκμηρίοις," "ς" "᾽" "ἡμέρα"

## [49] "τεσσαράκοντα" "ὀπτανόμενος" "αὐτός" "καί"

## [53] "λέγω" "ὁ" "περί" "ὁ"

## [57] "βασιλεία" "ὁ" "θεοῦ." "4"

## [61] "καί" "συναλιζόμενος" "παρήγγειλεν" "αὐτός"

## [65] "ἀπό" "Ἱεροσολύμων" "μή" "χωρίζεσθαι,"

## [69] "ἀλλά" "περιμένω" "ὁ" "ἐπαγγελία"

## [73] "ὁ" "πατήρ" "ὅς" "ἠκούσατέ"

## [77] "ἐγώ" "5" "ὅτι" "Ἰωάν(ν)ης"

## [81] "μέν" "ἐβάπτισεν" "ὕδατι," "ὑμεῖς"

## [85] "δέ" "ἐν" "πνεύμα" "βαπτισθήσω"

## [89] "ἁγίος" "οὐ" "μετά" "πολύς"

## [93] "ταύτης" "ἡμέρας." "6" "ὁ"

## [97] "μέν" "οὖν" "συνελθόντες" "ἠρώτων"

Certainly, parts of speech can be accessed in a similar way, via

parsed_text$upos. Not only this, though. If you look carefully at the

resulting POS tags, you’ll notice PROPN here and there. These are

proper nouns as detected by NER (named entity recognition) module of the

above function udpipe(). We can get all the names:

parsed_text$lemma[parsed_text$upos == "PROPN"]

## [1] "Ἰησοῦς" "Ἱεροσολύμων" "Ἰωάν(ν)ης" "ἐφ" "Ἰερουσαλήμ"

## [6] "Ἰουδαία" "Σαμαρεία" "Ἰησοῦς" "ἀφ" "Ἰερουσαλήμ"

## [11] "Ἰερουσαλήμ" "Πέτρος" "Ἰωάν(ν)ης" "Ἰάκωβος" "Φίλιππος"

## [16] "Βαρθολομαῖος" "Ἰάκωβος" "Ἁλφαίος" "Σίμων" "Ἰούδες"

## [21] "Μαρία" "Ἰησοῦς" "Δαυὶδ" "Ἰούς" "γενομένος"

## [26] "τοῦτ" "Χωρίος" "ἐφ" "Ἰωάν(ν)ης" "ἀφ"

## [31] "Ἰωσήφ" "ἀφ" "Ἰούδες" "ἐφ" "Ἰερουσαλήμ"

## [36] "Ἰουδαία" "Πόντος" "Φρυγία" "Αἴγυπτος" "Λιβύης"

## [41] "Ἰερουσαλήμ" "Ἰησοῦς" "Δαυὶδ" "Χριστός" "Ἅιδης"

## [46] "Ἰησοῦς" "Δαυὶδ" "Κάθος" "Ἰσραήλ" "Χριστός"

## [51] "Ἰησοῦς" "Πέτρος" "Πέτρος" "Ἰησοῦς" "Χριστός"

## [56] "κατ" "Πέτρος" "Ἰωάν(ν)ης" "Πέτρος" "Ἰωάν(ν)ης"

## [61] "Πέτρος" "Ἰωάν(ν)ης" "Ἰησοῦς" "Χριστός" "Ναζωραίος"

## [66] "Ὡραία" "Πύλη" "Πέτρος" "Ἰωάν(ν)ης" "Σολομών"

## [71] "Πέτρος" "Ἀβραάμ" "Ἰσαάκ" "Χριστός" "Μωϋσῆς"

## [76] "Προφήτης" "Σαμουήλ" "Ἰησοῦς" "Ἰερουσαλήμ" "Ἅννας"

## [81] "Καϊάφας" "Ἰωάν(ν)ης" "Ἀλέξανδρος" "Πέτρος" "Ἰσραήλ"

## [86] "Ἰησοῦς" "Χριστός" "ὑφ" "Πέτρος" "Ἰησοῦς"

## [91] "Ἰερουσαλήμ" "ἀλλ" "Πέτρος" "Ἰωάν(ν)ης" "ἐφ"

## [96] "Δαυὶδ" "Χριστός" "Ἡρῴδης" "Πόντιος" "Πιλᾶτος"

## [101] "ἀλλ" "Ἰωσήφ" "Βαρναβᾶς" "Σαπφείρης" "Σατανᾶς"

## [106] "Πέτρος" "ἐφ" "ἀλλ" "Πέτρος" "Παραγγελία"

## [111] "Ἰερουσαλήμ" "ἐφ" "Πέτρος" "Ἰσραήλ" "Ἰούδες"

## [116] "Ἰησοῦς" "κατ" "Φίλιππος" "Πρόχορος" "Νικάνορα"

## [121] "Τίμων" "Παρμενᾶς" "Νικόλαος" "Ἰερουσαλήμ" "Στέφας"

## [126] "Μωϋσῆς" "τούτος" "Ἰησοῦς" "Ἀβραάμ" "Μεσοποταμία"

## [131] "μετ" "Ἰσαάκ" "Ἰσαάκ" "Ἰακώβ" "Ἰωσήφ"

## [136] "Αἴγυπτος" "μετ" "Φαραώ" "Αἴγυπτος" "ἐφ"

## [141] "ἐφ" "Αἴγυπτος" "Χανάα" "Ἰακώβ" "Αἴγυπτος"

## [146] "Ἰωσήφ" "Φαραώ" "γένος" "Ἰωσήφ" "Ἰακώβ"

## [151] "Ἰακώβ" "Συχὲμ" "Ἀβραάμ" "Ἑμμώρ" "Αἴγυπτος"

## [156] "Φαραώ" "Μωϋσῆς" "Τίς" "ἐφ" "Μωϋσῆς"

## [161] "Σινᾶ" "Μωϋσῆς" "Ἀβραάμ" "Ἰσαάκ" "Μωϋσῆς"

At this point, two remarks need to be made. Firstly, some models were

trained without taking into account proper nouns as a separate category.

Consequently, they don’t recognize named entities at all. E.g. if you

use an alternative model for Ancient Greek, nemely

ancient_greek-perseus (which is larger and generally much better than

ancient_greek-proiel, by the way), then the word, say, Φιλίππος

(Philippos) will be recognized as NOUN rather than PROPN. Secondly,

as the above list clearly suggests, the NER module returns wrong answers

at times, e.g. the word τοῦτ is clearly misrecognized by the model.

If it is possible to extract the proper nouns alone, then it is

obviously also possible to get the lemmatized text without the proper

nouns, by replacing == (equals to) with != (is different) in the

snippet discussed above:

parsed_text$lemma[parsed_text$upos != "PROPN"]

Pre-processing text files

We’re ready now to apply lemmatization to all the texts in our corpus.

One additional step: we send an empty string to the text file

texts_lemmatized.txt in order to create that file (or to clean it if

it exists). The same with the file text_IDs.txt.

cat("", file = "texts_lemmatized.txt")

cat("", file = "text_IDs.txt")

Now the most difficult part of the procedure follows. It loops over all

the text files from the current directory – so please make sure that the

folder corpus contains all your texts and nothing else – and then for

each document, it runs the udpipe() function that lemmatizes the

texts. Not only this, since it also detects named entities (proper

nouns) that will be excluded from the texts a few lines later. Finally,

all the lemmatized documents are written (one document in a line) to a

joint text file texts_lemmatized.txt. However, since our texts might

be quite long at times – and many real-life topic models are indeed

based on long texts – one additional step is added to the pipeline,

namely each lemmatized text is split into 1000-word chunks. The

splitting procedure might seem somewhat obscure, but it basically runs

another loop and iteratively writes the next chunk to a joint file

texts_lemmatized.txt. Further details of text processing nuances will

be covered in a different post; for the time being I suggest copy-paste

the following code:

for(current_file in text_files) {

current_file = paste("corpus/", current_file, sep = "")

# let's say something on screen

message(current_file)

# lead the next text from file, keep it split into pars

current_text = readLines(current_file, encoding = "UTF-8", warn = FALSE)

current_text = paste(current_text, collapse = " ")

# run udpipe

parsed_text = udpipe(x = current_text, object = udmodel)

# get rid of proper nouns and punctuation

lemmatized_text = parsed_text$lemma[parsed_text$upos != "PROPN"]

# get rid of NAs (just in case)

lemmatized_text = lemmatized_text[!is.na(lemmatized_text)]

# splitting the string of lemmas into chunks of 1000 words each:

chunk_size = 1000

# defining the number of possible chunks

no_of_chunks = floor(length(lemmatized_text) / chunk_size)

# writing each chunk into a final txt file

for(i in 0:(no_of_chunks -1)) {

start_point = (i * chunk_size) + 1

current_chunk = lemmatized_text[start_point : (start_point + chunk_size)]

current_chunk = paste(current_chunk, collapse = " ")

write(current_chunk, file = "texts_lemmatized.txt", sep = "\n", append = TRUE)

chunk_ID = paste(gsub(".txt", "", current_file), sprintf("%03d", i), sep = "_")

write(chunk_ID, file = "text_IDs.txt", sep = "\n", append = TRUE)

}

}

## corpus/act.txt

## corpus/ap.txt

## corpus/I_cor.txt

## corpus/iac.txt

## corpus/II_cor.txt

## corpus/io.txt

## corpus/luc.txt

## corpus/mat.txt

## corpus/mr.txt

## corpus/rom.txt

We’re ready to build a document term matrix, as computer scientists

prefer to name it, or a table of word frequencies, as digital

humanists usually put it. At least two R packages can help build such a

matrix, namely the package tm and the package stylo. There are

substantial differences between these two packages in terms of their

aim, scope, ease of use, speed, and ability to process large datasets.

In this tutorial the fully-fledged text mining library tm will be

used. It’s true that this package might seem intimidating at times, but

it offers all we need (and much more) to process our corpus.

First we read the already created files texts_lemmatized.txt and

text_IDs.txt, followed by combining them into a data frame:

raw_data = readLines("texts_lemmatized.txt", encoding = "UTF-8")

text_IDs = readLines("text_IDs.txt")

data_with_IDs = data.frame(doc_id = text_IDs, text = raw_data)

Why data frame? That’s how tm likes it. Another thing that tm needs

at this stage, is a list of stopwords to be excluded from the documents.

If you downloaded the entire corpus from the repository, there should be

a file ancient_gr.txt with Ancient Greek stopwords. Let’s load the

file:

stopwords = readLines("ancient_gr.txt", encoding = "UTF-8", warn = FALSE)

The above stopwords are grabbed somewhere from the internet; the quality

of the list is difficult to assess, even if it looks very solid at a

glance. Alternatively, there exists an R package tidystopwords that

contains stopword lists for 110 languages. More importantly, here the

stoplists were generated automatically from the official release of

Universal Dependencies, which makes the final set of stopwords rather

reliable:

library(tidystopwords)

stopwords = generate_stoplist(language = "Ancient_Greek")

Mind that the previously loaded file ancient_gr.txt has just been

overwritten. It’s up to you which of the two solutions you pick. At the

end of this tutorial, yet another method of dealing with stopwords will

be discussed. As for now, we’re ready to activate the package tm,

followed by creating a corpus from the existing data frame

data_with_IDs:

library(tm)

corpus = Corpus(DataframeSource(data_with_IDs))

Now, a whole pre-processing chain follows. It is up to you which steps

you involve into your pipeline, it also depends on how clean is your

corpus, on the language, and even on the script (since some alphabets

make no distinction between lower- and uppercase). The following chain

is however fairly standard; as you can see, each subsequent line

overwrites the variable parsed_corpus, which means you can easily

switch off any of the lines by commenting it out (or deleting):

parsed_corpus = tm_map(corpus, content_transformer(tolower))

parsed_corpus = tm_map(parsed_corpus, removeWords, stopwords)

parsed_corpus = tm_map(parsed_corpus, removePunctuation, preserve_intra_word_dashes = TRUE)

parsed_corpus = tm_map(parsed_corpus, removeNumbers)

parsed_corpus = tm_map(parsed_corpus, stripWhitespace)

The final step is easy. We define the frequency threshold to get rid of

the rare words, and then we compute a document term matrix, cutting the

words below min_frequency:

min_frequency = 5

doc_term_matrix = DocumentTermMatrix(parsed_corpus,

control = list(bounds = list(global = c(min_frequency, Inf))))

Optionally, if you’re not sure whether the table really exits, and how

big it is, you might – just in case – check the dimensions of the

variable doc_term_matrix. The first value indicates the number of rows

(i.e. documents), the second counts the columns (i.e. words/terms):

dim(doc_term_matrix)

## [1] 112 1464

Training a topic model

With the matrix computed, we’re ready to take off. In order to train a topic model, we have to activate an appropriate R package, and to decide the number of topics we want to get:

library(topicmodels)

number_of_topics = 25

Finally, the main procedure follows, with some real-life parameters of the model specified as arguments of the LDA function:

topic_model = LDA(doc_term_matrix, k = number_of_topics, method = "Gibbs",

control = list(seed = 1234, burnin = 100, thin = 100,

iter = 1000, verbose = 1))

## K = 25; V = 1464; M = 112

## Sampling 200 iterations!

## Iteration 1 ...

## Iteration 2 ...

## Iteration 3 ...

## Iteration 4 ...

## Iteration 196 ...

## Iteration 197 ...

## Iteration 198 ...

## Iteration 199 ...

## Iteration 200 ...

## Gibbs sampling completed!

## K = 25; V = 1464; M = 112

## Sampling 100 iterations!

## Iteration 1 ...

## Iteration 2 ...

## Iteration 3 ...

## Iteration 4 ...

## Iteration 97 ...

## Iteration 98 ...

## Iteration 99 ...

## Iteration 100 ...

## Gibbs sampling completed!

If training took a considerable amount of time, it really makes sense to save the final model somewhere on disk:

save(topic_model, file = "topic_model_k-25.RData")

Now, a non-obvious step follows. Since the variable topic_model is

quite a complex R object, it might help to explicitly extract the

information about the distribution of words and the distribution of

topics from it:

model_weights = posterior(topic_model)

topic_words = model_weights$terms

doc_topics = model_weights$topics

And that’s all. Now we can start exploring the topics.

Digging into the topics

There exist a few ways to look into the trained topic model. An obvious intuition involves looking at a topic of choice, in order to see which words are formative for that topic, e.g. this gives us 10 most important words of the topic 5:

sort(topic_words[5,], decreasing = TRUE)[1:10]

## θεός λόγος ἀνήρ ὀνόμα αὐτούς λαλέω ἀκούω

## 0.04391631 0.03620324 0.03475704 0.02463363 0.02318743 0.02174123 0.02077709

## λαός πνεύμα ἁγίος

## 0.02077709 0.01884882 0.01643849

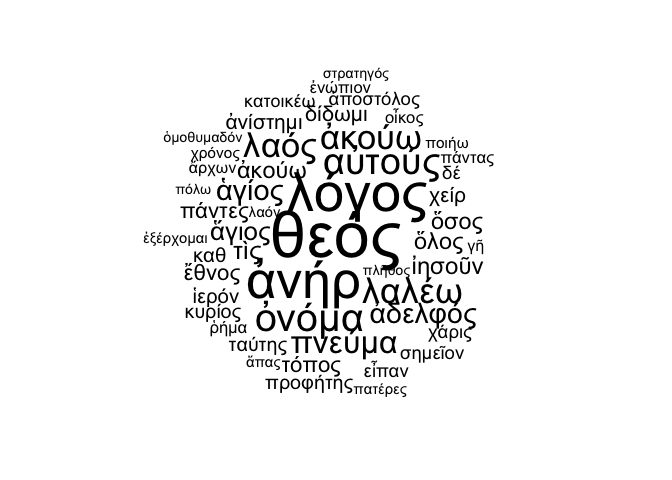

And here’s a more fancy way of showing the topic words, namely via a wordcloud visualization:

library(wordcloud)

# to get N words from Xth topic

no_of_words = 50

topic_id = 5

current_topic = sort(topic_words[topic_id,], decreasing = TRUE)[1:no_of_words]

# to make a wordcloud out of the most characteristic topics

wordcloud(names(current_topic), current_topic, random.order = FALSE, rot.per = 0)

Stopwords via TFIDF

In the above steps, there were at least a few potential issues that have

not been covered so far. One of them is the k parameter, or the number

of topics to be indicated before training an LDA model. In our model, we

used an arbitrary number of 25 topics, which might not be (and probably

is not) optimal. Please refer to the package ldatuning, and especially

its documentation, in order to explore ways of optimizing the k

parameter. Another potential issue is the stopword list that, again, is

often compiled from arbitrarily chosen sources. One of the alternative

ideas to identify the words to be excluded, is applying TFIDF weights to

the document term matrix and deciding a threshold below which a given

word falls into a stoplist category. Here’s the code to compute TFIDF

scores out of the doc_term_matrix (i.e. our document term matrix). The

last line trims down the original matrix to contain only the columns

with TFIDF higher than 0.3 (which is quite arbitrarily chosen, by the

way):

dtm_copy = as.matrix(doc_term_matrix)

dtm_copy[dtm_copy > 0] = 1

d = colSums(dtm_copy)

N = length(dtm_copy[,1])

idf = log(N / d)

tfidf = t( t(as.matrix(doc_term_matrix)) * idf)

average_tfidfs = colMeans(tfidf)

doc_term_matrix = doc_term_matrix[ , (average_tfidfs > 0.3)]

Mind that the last line overwrites the doc_term_matrix variable! Now

one needs to repeat the model training procedure. To this end, execute

the above code, starting from the snippet topic_model = LDA(...).

Happy modeling!

Putting it all together

In this tutorial, we went through the code step by step. Understandably, one would like to have the code consolidated into a single snippet. Please find it below. It’s basically the same code, except that I cleaned it up a bit, and moved up the key parameters to be set by the users. The resulting topic model can (I’d say should) be saved on disk, because it makes little sense to train it again and again:

library(udpipe)

library(tidystopwords)

library(tm)

library(topicmodels)

##### set the parameters ##################################

udmodel = udpipe_download_model(language = "ancient_greek-proiel", model_dir = tempdir())

stopwords = generate_stoplist(language = "Ancient_Greek")

min_frequency = 5

number_of_topics = 25

chunk_size = 1000

###########################################################

text_files = list.files(path = "corpus")

cat("", file = "texts_lemmatized.txt")

cat("", file = "text_IDs.txt")

for(current_file in text_files) {

current_file = paste("corpus/", current_file, sep = "")

# let's say something on screen

message(current_file)

# lead the next text from file, keep it split into pars

current_text = readLines(current_file, encoding = "UTF-8", warn = FALSE)

current_text = paste(current_text, collapse = " ")

# run udpipe

parsed_text = udpipe(x = current_text, object = udmodel)

# get rid of proper nouns and punctuation

lemmatized_text = parsed_text$lemma[parsed_text$upos != "PROPN"]

# get rid of NAs (just in case)

lemmatized_text = lemmatized_text[!is.na(lemmatized_text)]

# splitting the string of lemmas into chunks

# defining the number of possible chunks

no_of_chunks = floor(length(lemmatized_text) / chunk_size)

# writing each chunk into a final txt file

for(i in 0:(no_of_chunks -1)) {

start_point = (i * chunk_size) + 1

current_chunk = lemmatized_text[start_point : (start_point + chunk_size)]

current_chunk = paste(current_chunk, collapse = " ")

write(current_chunk, file = "texts_lemmatized.txt", sep = "\n", append = TRUE)

chunk_ID = paste(gsub(".txt", "", current_file), sprintf("%03d", i), sep = "_")

write(chunk_ID, file = "text_IDs.txt", sep = "\n", append = TRUE)

}

}

message("NLP done!")

raw_data = readLines("texts_lemmatized.txt", encoding = "UTF-8")

text_IDs = readLines("text_IDs.txt")

data_with_IDs = data.frame(doc_id = text_IDs, text = raw_data)

# create a corpus from a data frame

corpus = Corpus(DataframeSource(data_with_IDs))

# pre-processing chain

parsed_corpus = tm_map(corpus, content_transformer(tolower))

parsed_corpus = tm_map(parsed_corpus, removeWords, stopwords)

parsed_corpus = tm_map(parsed_corpus, removePunctuation, preserve_intra_word_dashes = TRUE)

parsed_corpus = tm_map(parsed_corpus, removeNumbers)

parsed_corpus = tm_map(parsed_corpus, stripWhitespace)

# document term matrix

doc_term_matrix = DocumentTermMatrix(parsed_corpus,

control = list(bounds = list(global = c(min_frequency, Inf))))

# training a topic model

topic_model = LDA(doc_term_matrix, k = number_of_topics, method = "Gibbs",

control = list(seed = 1234, burnin = 100, thin = 100, iter = 1000, verbose = 1))

# extracting topic distributions

model_weights = posterior(topic_model)

topic_words = model_weights$terms

doc_topics = model_weights$topics

The trained topic model can be further inspected by producing wordclouds and, more interestingly, by interpreting the distribution of topics in particular (groups of) documents. This however will be covered in a different tutorial.

-

It is assumed that the relevant packages are already installed on your machine. Otherwise, you would need to install them first, by typing

install.packages(c("topicmodels", "udpipe", "tm", "tidystopwords"))in your R console. ↩ -

To get the list of available language models provided by the package

udpipe, typehelp(udpipe_download_model); the detailed descriptions of the respective models are posted here: https://universaldependencies.org ↩